Los Angeles describes itself as a ‘city on the move’, a city that prides itself on having some of the most complex and interesting transportation infrastructure one can experience. To be an Angeleno is to have to move, to spend time on a freeway, a train, a bus. Indeed, Reyner Banham described Los Angeles’ transportation as inherent to its design from the very beginning. The Spanish built networks of roads like the Camino Real to connect the missions and assistencias through California. Roads in the mid 19th century were constructed to connect the Ranchos that orbited the Pueblo. The development of the unincorporated cities that would make up the county resulted in the use of newer technologies, namely the trolley. This brought about an era marred by tycoon based warfare as everybody and their cousin sought to connect their little town to the bigger town or the port or the beach. So, the commute is somewhat in the DNA of Los Angeles having taken a shift throughout time. The changes in our nature of work and commerce have brought about different effects on the way we experience this urban landscape socially and psychologically.

Commuting sucks no matter how you do it or for what distance. We could plug in the stats of how much time people spend in traffic, how much environmental damage has to be mitigated, and how much it costs just to commute. However, such arguments have proven to be unpersuasive. Having to drive to work in a car in a city like Los Angeles, ostensibly designed around the idea of the car, is anxiety inducing. The idea of commuting by car has come to define an entire ecology we live within and around. The ecology of the commute is the domain of commercialized thoroughfares, combination housing and commercial spaces, endless coffee shops and restaurants, and micro-transit zones. Walkable zones (Fewer than one hundred thousand Angelenos commute to work on foot) only exist around areas of interest and major landmarks. All else is cars and roads.

I have friends now who are perplexed and anxiety-ridden over the concept of having to have an actual commute every morning. They feel, and strongly desire, they should be able to work and live in close proximity. They want no commute at all. As much as I believe this is a current impossibility, I don’t disagree with them. The morning commute has been such an integral part of LA life for so long that it has broken containment and become a sort of meme to people who don’t even live here. I’ve met people from other countries who know about as much about the 405 as I do. Growing up the way to know you had reached adulthood was not only that you had a car and a job but also that you had some sort of commute. To have a job is to have to go someplace to work. Recent times have gotten us to rethink the idea of labor what work means, much less what it means to be productive. A majority of work based tasks can be completed anywhere. We have technologies that have made us more productive than we reasonably need to be. Aside from people working in specialized careers or the service industry there is not much need for commuting to an office. But it’d be bad I guess if we got rid of all the commercial properties. Imagining what would happen if New York had to get rid of 40% of its commercial properties and parking lots is an interesting proposition. One of the major reasons employers were so adamant about people returning to work in the office post-pandemic was the economic shock caused by so many people working from home. The commuter economy is huge.

This is not by accident. Anything and everything you see and live around and do is designed by and built by human beings. This human being had a worldview and point they were trying to make about the thing they made. To live in a multi-family apartment building named “The Gardens at Redondo” is not just pure marketing. It is the conclusion to living in a designed place built for people who could afford to and desired to live in a place called “The Gardens at Redondo”. This idea extends to the larger community and eventually a city itself. This intent did not originate recently it’s existed throughout the history of Los Angeles with the caveat that every city and community in the county came to define itself through societal and economic activities. Throughout the middle of the 20th century and well into the 80s and 90s, Los Angeles faced numerous changes in its own constructed destiny. For one, white flight devastated the inner city. The construction of suburbs led to the major city having a hub like effect. The inner city remained the place where jobs were but they now had to be driven to from larger distances. A rapid period of professionalization in the latter decades meant more people working in skyscrapers, business parks, and office campuses. Freeways were built largely to serve the needs of suburbanites transiting into and out of Los Angeles as opposed to across. As important as freeways are to the aesthetic landscape of the city, they aren’t nearly as important to people who live within it.

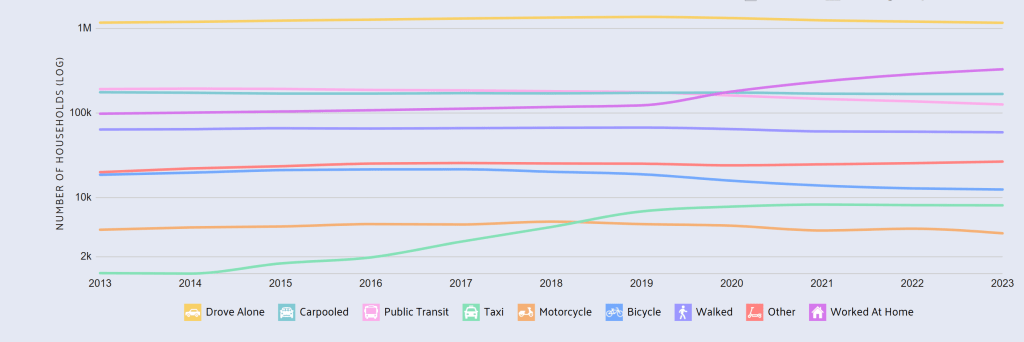

According to the Census Bureau, the average Angeleno has a commute time of a half hour or so. Additionally, about 60% of commute in the city is by car. This number has remained relatively steady for the past decade despite the pandemic resulting in changes to work environments and increases in the amount of people working from home. Interestingly, the use of public transportation has been decreasing steadily in recent years. Probably due to urban public transportation having the worst PR of any public good. Los Angeles public transportation is objectively speaking pretty good. This does not matter when people believe your light rail systems are “rolling homeless shelters” and buslines are “dens of crime”.

If you want to live in the type of environment where your commute to work is non-existent or at least within your own community you’d need a bit of imagination. Additionally, in a place like LA, you might have to be prepared to make peculiar sacrifices. The amount of times I’ve witnessed people take subpar living conditions just to be close to where they work can be counted on both hands.

First, a primer. For many, the prospect of defining communities as ‘walkable’ carries the weight of gentrification along with it. To litigate this any longer goes beyond the scope of this writing, but we must understand that in the current world we live in the reconstruction or redesign of an entire community in order to pursue environmental improvement, quality of life, or whatever else inevitably means that people will be marginalized in some way. In order to fix the issues inherent to capital focused urban design we have to perform major structural changes to society at large. So, because it is much easier to build a better building than it is to radically reshape a government that is what people are more likely to choose.

A way to start would be to redefine how we look at the construction of our built environment. The city of Los Angeles is 500 square miles in size. Roughly 1% of the US population lives in Los Angeles (about 1 in 95 Americans). Rather than thinking of it in the macro sense we could try looking at a place like LA as an interconnected network of communities.

Some developers have taken to constructing heavy buzz word laden micro-communities catered around specific lifestyles. Whole towers of mixed commercial/residential constructed around people who work from home and want to decrease their commuting footprint or eliminate it entirely. If people have to go anywhere they ride a rent-a-scooter or something or walk.

The community colloquially known as Silicon Beach, formerly the site of Hughes Aircraft, has attempted to capitalize on the modern demand for walkable, livable, vibrant communities that combine places of work with housing. The area is at the foot of a private university (Loyola Marymount) and less than a full mile from the coastline. Nothing about this area is remotely affordable.

To a lesser extent we could take a lesson from the planned communities that often surround, and in some ways come to define, universities. Universities have the distinct advantage of having a captive group of residents. They can create and tailor specific economic and social needs because predicting the age group, income levels, and amount of free time students have is easy. University districts also often feature at least some of the area being denied car access making them walk or micro transit only. the university district is then connected to the broader area via light rail, bus, electric golf cart services, rickshaws, etc.

Regardless of the method chosen, these communities would require external connection. This requires policy. A recently passed bill, SB79, allows cities in California to place multi-unit dwellings within a specified distance of transit stops. This should prompt developers and zoning commissions to redevelop mass transit corridors in urban areas to better serve people who live there rather than packing these areas with commercial properties that sit vacant for years awaiting a tenant. Similar bills could be proposed that would spur interest in creating new communities that are livable rather than creating shopping districts along transit routes that create congestion and serve no purpose when dormant.

We can make these changes and we can definitely afford to consider their expansion. Cities have to work for their inhabitants. One of the ways to remedy the pain of commuting is to change how we think of community design and adopting environments our technological advancements have afforded us. We most likely cannot redesign urban areas to eliminate the commute altogether but we can certainly connect communities in ways that makes commuting less of a chore.